Seraphic College

Seraphic College

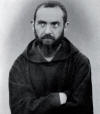

The convent of San Giovanni Rotondo included a small seminary called “Seraphic

College”. Padre Pio was assigned the direction, including spiritual direction,

and some teaching.[1]

Aurelio Di Iorio da Sant’Elia a Pianisi studied under Padre Pio from 1916 to

1918. Padre Aurelio reported: “He had a superficial way of teaching. He taught

history and grammar, but he knew little of the former and none of the latter.

None less we boys were attracted to him. The key to his charm was his humanity.

His sanctity was his humanity.”[2]

Paolino also was his student: “He had weekly conferences were he introduced us

to the love of the Lord.”[3]

Padre Pio was so committed to help the student that he wrote to Padre Benedetto

on March 6, 1917: “I have a vivid desire to offer myself as a victim for

perfecting this college that I love tenderly.”[4]

Federico Carrozza da Macchia Valfortore, another student at the time: “He was

always praying, night and day. In our midst, while talking to us, he held the

rosary in the right hand, hidden in the folds of his habit. He spent long hours

on his knees. In the refectory he took a few mouthfuls.[5]

Aurelio reported that he and the other students in the seraphic college one

morning saw Padre Pio’s bed completely turned upside down and twisted. Also, the

curtain and the rod holding the iron curtain were all twisted up like a piece of

curly hair. The rod was thick as a finger, and was all turned and twisted. “We

were really scared.” When Padre Pio came along and saw the devastation, and the

students scared, he said: “Don’t make a big deal of it. Barbablu’ messed up

everything.”[6]

July 29, 1918: “It has been a week that I have been alone with the students,

because Padre Paolino is out. I hope that he will come back this evening. He

will leave again on Saturday.”[7]

In September 1918 the Spanish fever was still raging in Italy. In those few

weeks 200 people had died of Spanish fever in San Giovanni Rotondo.

[8]

In the college, the two dozen or so boys were almost all ill. The doctor

prescribed injections. Because he was understably overworked, he thought Padre

Paolino and Padre Pio how to give the injections. Since alcohol was not

available, the doctor left some carbolic acid to sterilize the site of the

injection.[9]

Padre Pio obtained “secretly” through Maria De Vito from her cousin Valentino Vista, a pharmacist in Foggia a little bottle with four grams of pure carbolic acid “for the disinfection of the syringes and also four grams of veratrine.[10]

Towards the end of June 1920, Mons. Salvatore Bella, bishop of Foggia, took to the Holy Office the deposition of the two pharmacists who feared Padre Pio was artificially causing the stigmata with the aforementioned drugs.[11]Padre Pio explained it under oath to Mons. Rossi: “The secret was requested to conceal from those who would transport it that it was a dangerous medicine, without a doctor’s prescription. The purpose was to disinfect he syringes. In a boarding school for boys there is often such necessity.”[12]

About the veratidine Padre Pio testified: “I requested it because Padre Ignazio

made me sniff once such powder. I wanted to use it during recreation. A small

dose of this powder prompts immediate sneezing.”[13]

Padre Pio’s family had also been stricken. On September 22 died Padre Pio’s

nephew Pellegrino, and on September 25 his sister Felicita, the mother of

Pellegrino, died of Spanish fever too. Padre Pio’s mother also contracted the

illness and for weeks was gravely ill.[14]

Padre Pio had it in moderate form, and was sick in bed for September 5 through

the 16th. He restarted celebrating mass on September 17.[15]

Because most of the friars were in military service,

at that time the convent consisted of

three friars: Padre Paolino, superior, Padre Pio, and Brother Nicola alms

seeker. There were also a dozen of young students of the seraphic college.

[16]

Transverberation

of the heart

Transverberation is a wounding of the heart, as a reward by God for loving Him.

It manifests itself by physically passing through the heart.[17]

Several saints experienced it. Some few names: Theresa of Avila, Therese of

Lisieux, Veronica Giuliani, Marguerite Marie Alacoque, Gerardo Majella, Joseph

of Cupertino, Francis de Sales, Philip Neri, Jane Francis de Chantal, Lutgarde,

Charles of Sezze.

On August 5-7, 1918 and in December 1918 Padre Pio had transverberation of the

heart.

Padre Pio described under obedience his transverberation in a letter to Padre

Benedetto on August 21, 1918: "The evening of the fifth I was hearing the

confessions of the boys, when a celestial personage, holding a very long sharp

pointed steel blade which seemed to emit fire, hurled it into my soul with all

is might. All done in a split of a second everything in my inside was lashed by

fire and steel. I felt I was dying. I asked the student to leave, because I was

not feeling well and I didn’t have any strength to continue. The agony continued

without ceasing until the morning of August 7. From that moment on I feel an

open wound which causes me to suffer continual pain."[18]

Padre Federico Carozza da Macchia Valfortore, a capuchin friar himself, in later

years revealed that he was the student present at the transfiguration of Padre

Pio. He didn’t tell anybody to avoid becoming center of attention. He was in the

college also at the time of the stigmatization.

Padre Agostino to Padre Pio on August 24, 1918: “August 6 was the feast of the

Transfiguration. Jesus wanted to transfigure your spirit and inflict on you a

wound that only He can heal.”[19]

Padre Benedetto on August 27: “All that happens in you is a consequence of love,

of the vocation to be co-redeemer.”[20]

After the Transverberation Padre Pio was left into “the dark night of the soul”

for several weeks. God seemed to have abandoned him.[21]

The stigmata are the bodily wounds on the hands, feet and side corresponding to

those inflicted on Jesus at the Crucifixion. Notable stigmatics were Francis of

Assisi, Rita of Cascia, John of God, Gemma Galgani, Veronica Giuliani, Catherine

of Siena.

Saint Francis of Assisi received the stigmata on Saturday September 14, 1224,

feast of the triumph of the Cross, on Mount Verna, town of Chiusi della Verna,

in Tuscany, Italy.

The

spot of the stigmatization of Padre Pio

The

spot of the stigmatization of Padre Pio

It all happened the morning of September 20, 1918, between 9 and 10. Padre Pio was praying in the choir after Mass. [22] He was kneeling on the upper row of stalls near the window,[23] on “the vicar’s bench”.[24]

Padre Pio was alone. He saw a

“mysterious personage” bearing five wounds. He was terrified and fainted. When

he recovered his senses, his hands feet and side were dripping blood. The pain

was immense. He slowly got up and dragged himself, step by step on the wounded

feet, to his cell where he tried to control the bleeding and clean up.[25]

The Crucifix in the choir has four nails, two for the hands, and two for the

feet. Instead of the customary three.[26]

_small.jpg)

The only picture of the wounds on the hands

The only picture of the wounds on the hands

Padre Pio did not tell anybody about it. How did people around him find out?

![]() The habit that Padre Pio was wearing at the time of the stigmatization

The habit that Padre Pio was wearing at the time of the stigmatization

Padre Paolino had gone to San Marco in Lamis to preach and confess in

preparation of the fest of St. Matthew.[27]

Brother Nicola da Roccabascerana was in the countryside in search of alms[28]

[29]

or in the kitchen[30].

The students had a vacation day and were staying in the backyard.

[31]

The first to notice the stigmata were the devout women in church.[32]

One of his spiritual daughters, Vittoria Ventrella, reported that “My sister

Filomena went to the convent on September 20, 1918, and was the first to notice

that the Padre had received the wounds, because she saw on his hands the red

marks similar to the marks that we see on the statue of the Sacred Heart. She

came home and told us.”[33]

Another spiritual daughter, Nina Campanile, went to the convent the morning of

September 21, to give Padre Pio an offering for a Mass to be said by Padre Pio.

In the sacristy, when she gave the offering she noticed a red mark on the back

of his hand. She said: “Padre, did you burn your hand?”

He did not answer. But when she tried to kiss the hand Padre Pio said:

“If you only knew the embarrassment you cause me!”[34]

When Nina reached home, she told her mother that Padre Pio has the stigmata like

St. Francis of Assisi.[35]

The next day, the 22nd, she went to the convent again and told the

superior: “Padre Paolino, do you know that Padre Pio has the stigmata?” Padre

Paolino smiled incredulously.[36]

Maria Campanile later committed to paper her memories of those days.[37]

Filomena Ventrella too went to Padre Paolino to inform him that Padre Pio

had the stigmata.[38]

Padre Paolino’s testimony: “I started thinking: “How can be possible that Padre

Pio has received the stigmata without me realizing it? I am always with him’. I

went in Padre Pio’s room without knocking at the door. He was writing at the

desk. When he saw me he got up. I asked him to continue writing. I got closer,

and first saw the wound on the back and on the palm of the right hand. Then I

saw the one on the back of the left hand. The same day I wrote to Padre

Benedetto, Provincial in San Marco La Catola, telling him what I had seen, and

asking him to come to San Giovanni Rotondo as soon as possible. To my

astonishment and disappointment he didn’t come. He sent me a letter where he

seemed not to give importance to what had happened. He only recommended me to

keep absolute silence over the issue.”[39]

[40]

Emilio da Matrice, at that time a fifteen years old student of the Seraphic

College, testified: “The morning of September 21, 1918, as soon as we approached

Padre Pio, we realized he had a wound on the palms of his hands, and was walking

with a certain difficulty. We learned only a few days later, from Padre Paolino,

that he had received the Lord’s wounds from[41]

the Crucifix in the choir.”

In a letter to Padre Benedetto on October 17, 1918, about a month after the

event, Padre Pio gave him a hint: “A mysterious individual wounded me all over.

Please come help me.

All my inside rains blood and I am forced to see it flow outside.

For pities sake I beg that ceases this torment, this condemnation, this

humiliation, this confusion!”

[42]

Padre Benedetto was in San Marco La Catola. He didn’t go to San Giovanni Rotondo

as requested, but sensed what had really happened, and wrote to Padre Pio on

October 19: “Tell me exactly what happened. I want know thoroughly everything,

under holy obedience.”[43]

Padre Pio wrote to Padre Benedetto under obedience on October 22:

“It was the 20th of last month and I was in the choir after Mass. It

was

the Friday after the feast of the stigmata of Saint Francis. Suddenly I was

wrapped in a sea of blazing light. In that light I saw a mysterious individual,

similar to the one I had seen the evening of August 5. He had hands, feet and

side dripping blood. From his wounds came rays of very bright white light that

penetrated my hands, my feet, and my side. They were like blades of fire that

penetrated my skin piercing, cutting, and breaking. I felt that I would die. The

pain was immense. The wounds were bleeding, especially the one on the side of

the heart. I had barely the strength to drag me to my cell to clean my clothes

all soaked in blood." Padre Pio concludes:

“Oh my God, how much confusion and humiliation I feel in having to show what You

have done in this poor creature of yours!”[44]

On December 20, 1918, Padre Pio wrote to his spiritual director Padre Benedetto:

“For several days I have been feeling like an iron blade penetrated the lower

part of my heart and extended transversally to the right shoulder. It gives me

an atrocious pain and doesn’t let me rest. What is this? This new phenomenon has

started after I saw the same mysterious personage that I saw on August five and

six and in September; of which I have written to you, if you remember, in other

letters.”[45]

According to the experts of mysticism this was the final seal of love, were

Padre Pio was completely transformed in a living image of Jesus.[46]

Padre Paolino da Casacalenda, the superior of Padre Pio, examined repeatedly the

chest wound, and reported in his memories: “The wound on the left side of the

chest has the form almost of an X. From that fact, one has to deduct that the

wounds are two.”[47]

The wounds created uneasiness in Padre Pio and in the friars. Padre Pio had to

continue his daily routine with the student of the seraphic college, while

dealing with the excruciating pain and the dripping of the blood. He started

wearing a green shawl trying to hide the hands under it. For mass he used a

vestment with extra-long sleeves, than he used full woolen gloves, and then half

gloves. He would remove them before the Canon and put them back after communion.

On the side wound he put a linen cloth, and on the feet he started

wearing socks. Padre Pio’s humility, simplicity and obedience were unchanged. He

would say to Padre Agostino: “Pray and have people pray for my conversion.”[48]

He went through desolation, aridity and scruples. “I see only darkness in my

soul. Who knows if God is happy with me.”[49]

On March 3, 1919 Padre Benedetto examined the wounds and sent a letter to Padre

Agostino: “They are real wounds, perforating the hands and feet. I have also

observed the side wound: it is a real gash that bleeds continuously either blood

or serum.”[50]

On April 24, 1919 Padre Benedetto informs the Padre Generale in Rome, explaining

what he had seen, and that he had not informed him before, because of the

sensitivity of the issue.[51]

The friars had no idea if the wound could be infected or contagious, since Padre

Pio had been diagnosed in the past as probably having tuberculosis. And the

Spanish fever was still raging or. An answer could come only from doctors.[52]

On May 1, 1919 Dr. Angelo Maria Merla was the first doctor to see Padre Pio

after he received the wounds. He was the town’s doctor, and also the mayor of

San Giovanni Rotondo. He went to the convent by request of Padre Paolino di

Tomaso da Casacalenda, the Padre Superior. He declared that the lesions were not

the result of tuberculosis, but that he could not say with any certainty what

caused them without extensive tests.[53]

On May 15 and 16, 1919, Prof. Luigi Romanelli, head physician of the Hospital in

Barletta, by disposition of Padre Benedetto di San Marco in Lamis, Provincial

Superior of the Capuchins, did a physical on Padre Pio, examining the wounds. He

wrote a report that was sent to the Superior General in Rome.[54]

He wrote in his report: "The lesions on the hands are covered by a red brown

membrane, without bleeding, no edema and no inflammation of the surrounding

tissues.

The pigmented areas are membranes covering a hole. There was no bone resistance.

I am certain that these wounds are not superficial because, putting my thumb in

the palm of the hand, and the index finger on the back, and applying pressure, I

have the exact perception of a void existing."

[55]

“The wounds on the feet are circular, with a diameter of about 1 ½ inches,

covered with red lucent membranes, with sharp edges and surrounded by normal

tissue. They are located in the area of the second metatarsal bone.[56]

“On the left side of the chest, in the area of the sixth intercostal space,

there is a linear slash wound of about three inches, leaking out arterial

blood.”[57]

"The etiology of the lesions of Padre

Pio is not natural. The agent producing those lesions needs to be searched, make

no mistakes, in the supernatural. The fact in itself it's a phenomenon that

cannot be explained with the sole human science."[58]

[59]

[60]

In 1919-1921,Cardinal Augusto Silj, Prefect of Apostolic Signature, the Supreme

Tribunal of the Holy See, visited with Padre Pio several times, each time

expressing a very positive opinion to Pope Benedict XV.[61]

July 1919: Dr. Amico Bignami, professor of medical pathology of the University

of Rome, an atheist, examined Padre Pio by disposition of Padre Venanzio da

Lisle, Superior General, and of Padre Giuseppe da Persiceto, General Procurator

of the Capuchin Order. On July 26, 1919 he gave a written report of his

examination.

"The lesions on the hands, feet and side can be explained as unconsciously

self-produced by autosuggestion, and kept artificially with repeated

applications of tincture of iodine." He also stated: “I do not understand how

these wounds have persisted for nearly a year now without getting better or

worse.” Bignami also commented: “The expression of Padre Pio’s face is full of

goodness and sincerity and leads me to the positive exclusion of a simulation”.[62]

[63]

Bignami also ordered the wounds bandaged and sealed for eight days under

supervision of a sworn committee. When the bandages were unsealed and removed

eight days later “the wounds remained the same.”[64]

[65]

[66]

The committee was composed of Padre Paolino da Casacalenda, Padre Basilio da

Mirabello Sannitico, and Padre Ludovico da San Marco in Lamis. Padre Paolino

wrote in his memories: “I am particularly grateful to Dr. Bignami. Without his

order I would never had a chance to see the wounds. I was particularly impressed

by the side wound. It has almost a form of an X. That means that they are two

wounds.” In fact it was consequence of two separated mystical events: the

transverberation of August 5, 1918, and the stigmatization of September 20,

1918.[67]

On October 9 and 10, 1919, Dr. Giorgio Festa, a surgeon in private practice,

well known in Rome at the time, examined the wounds by disposition of Padre

Venanzio da Lysle, Superior General of the Capuchin Order.

He made three examinations. The last was in 1925.[68]

[69]

On October 28, 1919, Dr. Festa, back in Rome, wrote a report of his examination,

and gave it to the superior general of the Capuchin order.

“In the palm of the left hand there is a circular lesion a little less than 1

inch in diameter. The lesion has a red brown color and is covered by a blackish

crust. The lesion doesn’t seem very deep. The back of the left hand has a lesion

similar to the one on the palm . The lesions on the right hand have the same

characteristics of the left hand.

The dorsal and plantar sides of the feet have circular lesions similar to the

ones on the hands. Applying a light pressure on the lesions elicits a sharp

pain. While examining the lesions ooze serum and blood. The skin surrounding the

lesions shows no signs of edema, infiltrate, or inflammatory reaction.

Le lesion on the left side of the chest, transversal, about two fingers below

the nipple, has the form of a cross, with the long arm measuring about little

less than three inches, and the short arm about 1 ½ inches. The lesion is

superficial and still emits drops of blood, more than the other lesion.

The lesions appeared all together on September 1918, 13 months ago, and show the

same freshness as they had just appeared. In all this months they have not shown

any tendency to cicatrization.

My opinion is that they were not originated by a cutting object or by applying

chemical substances. The action of chemicals would have influenced also the

surrounding tissues, which are normal. Padre Pio has applied iodine every couple

of days to limit the loss of blood. However he hasn’t applied any for more than

3 months, by disposition of his superiors, and the lesions present the same

characteristics as before.

My conclusion is that the lesions and the hemorrhage of blood have an origin

that our knowledge is very far from explaining. The reason for them is well

above the human science.”[70]

[71]

Padre Pietro da Ischitella

Padre Pietro da Ischitella

About the depth of the lesions, dr. Festa wrote that Padre Pietro da Ischitella,

the provincial superior had observed the lesions few months after the event and

had clearly the impression that the lesions went through the whole hand. Dr.

Festa continued: “I have personally questioned Padre Pietro da Ischitella, and

he told me verbatim: ’If a superior authority asks me I can declare and confirm

swearing that looking at the wound from the palm side one can easily see

through, recognizing a writing or an object positioned on the other side.’ “[72]

Dr. Andrea Cardone from Pietrelcina, who was friend and physician of Padre Pio

for many years, testified in 1968: “In both hands exist holes a bit larger than

half inch, passing through the palm of the hands to the other side; so that one

could see light passing through. And with pressure the fingertips of my thumb

and pointer touched each other.”[73]

In July 1920 the professors Giorgio

Festa and Luigi Romanelli did

follow up examinations of the wounds.

They did not perceive any interruption in the bones of the hands and of the

feet.[74]

Reported by Dr. Festa: A colleague of mine asked Padre Pio : "Why the lesions

are here and not in other parts of the body?" Answer: "You are a doctor. You

should tell me why they should have been in other parts of the body and not

here."[75]

[76]

[77]

The colleague of dr. Festa was dr. Bignami.[78]

[79]

Dr. Alberto Caserta of Foggia did x-rays of the hands of Padre Pio on October

14, 1954. The radiographs did not show interruptions in the bones.[80]

Padre Gerardo greeting Padre Pio, and one of his books

about the stigmatization of Padre Pio

Padre Gerardo greeting Padre Pio, and one of his books

about the stigmatization of Padre Pio

Regarding the chest wound, Padre Gerardo Di Flumeri has collected 14

descriptions of the direct observations of the examining physicians and of the

friars in contact with Padre Pio. They vary from a linear wound to one X shaped.[81]

Intigrillo: “The lesion on Padre Pio’s side will always be the subject of

discussion, with regard to both shape and exact position.”[82]

On November 19, 1919, the Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, Secretary of State, wrote to

the superior of the Capuchins, to recommend the Rosi family, who wanted to

confess and receive the Communion from Padre Pio, and also to ask him to pray

for the Pope’s intentions and for his own. He also asked for some little object

from Padre Pio for his niece Antonia Veda.[83]

[84]

[85]

Costa

In 1919, Mons. Alberto Costa, bishop of Melfi and Rapolla after visiting with

Padre Pio he wrote: “I am convinced of the holiness of Padre Pio. His life is

totally consecrated to the glorification of God and the conversion of the

sinners. My impression can be boiled down to one: to that of having talked to a

saint.”[86]

[87]

On March 24-27, 1920, Archbishop Anselm Edward Kenealy, of Simla, India, who was

himself a Capuchin and a prelate, examined Padre Pio by request of Pope Benedict

XV. Mons. Kenealy was known to be skeptical regarding mystical phenomena. He

spent five hours with Padre Pio.[88]

He reported: “I wanted to see the wounds of Padre Pio because I am resistant to

believe in things if I have not seen them with my own eyes. I went, I saw, I was

conquered (Veni, Vidi, Victus sum). I

am deeply convinced that we have a true saint here. The Lord, with the five

wounds of the Passion has given him great gifts, and he is completely at ease.

If he knows how to suffer, he also knows how to laugh.”[89]

[90]

[91]

On May 20, 1920, not completely satisfied, the pope sent archbishop Bonaventura

Cerretti, secretary of the Congregation for Extraordinary Ecclesiastical

Affairs, who’s Prefect was Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, to examine Padre Pio. He

reached the convent on May 24. Padre Onorato wrote that Cerretti came dressed as

a simple priest, showed the letter of the Holy Office and his episcopal cross,

and asked to examine Padre Pio. He was deeply impressed, wrote in the guest book

an expression of admiration, asked the prayers of Padre Pio, and gave the Pope a

very positive evaluation.[92]

[93]

Bishop Angelo Poli (or Police), apostolic vicar of Allahabad, India, visited

Padre Pio in October 1920. He wrote on November 2, 1920: “I came, I saw, and I

was conquered. Not the slightest doubt remains in me: the finger of God is here

(Digitus Dei hic est). Seeing Padre

Pio one feels overwhelmed by the presence of supernatural, and at the same time,

his natural simple attitude inspires confidence.”[94]

[95]

[96]

On February 17, 1921, Padre Pio expressed in a letter to Mons. Poli his desire

to become a missionary: “… I have made persistent pressure on my director to let

me be one of your missionaries, but he finds that I am unfit for it.”[97]

On April 18, 1920. Padre Agostino Gemelli, Franciscan friar, physician and

psychologist, went to the Convent. He said: "Padre Pio I came for a clinical

exam of your lesions." Padre Pio asked: "Do you have a written authorization?"

"No" replied padre Gemelli. "Then I'm not authorized to show them to you"

concluded Padre Pio. The conversation did not last more than two minutes: a few

words, no examination of the stigmata, and Padre Pio dismisses him. But the next

day Gemelli sends a personal letter to the Holy Office declaring the stigmata

“fruit of suggestion”, and two months later he sends a second one with specific

advice on the measures to take.[98]

Gemelli stated in a written report that he had examined Padre Pio, and described

in details the wounds, but it is certain that no such examination took place. He

also said the he had done a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation. Padre

Benedetto da San Marco in Lamis, who was present at the meeting, wrote a

detailed report, confirming that Gemelli hadn’t examined Padre Pio. Gemelli’s

criticism was instrumental for the measures taken by the Vatican against Padre

Pio.[99]

[100]

[101]

Gemelli’s report submitted to the Holy Office has never been released. In 1931

Cardinal Michele Lega told Padre Luigi da Avellino: “It was terrible. If you

could read it, it would change your mind about Padre Pio.”[102]

In later years Gemelli had “somewhat” changed his position about Padre Pio.

Gemelli died July 15, 1959. It is reported that Padre Pio told another friar

that he assisted and confessed Padre Gemelli in bilocation in his final moments.[103]

On July 12, 1920, Padre Luigi Besi, General Postulator of the Passionists, made

an apostolic visitation by disposition of Pope Benedict XV. He went unannounced.

When he reached Foggia by train, he was greeted by a Capuchin friar who told

him: “Padre Pio has asked for a friar to go to Foggia and pick up a Passionist

who had been sent by the Pope. I am here to accompany you to the convent.”[104]

[105]

Besi was impressed. He wrote that Padre Pio “was privileged by God, as was St.

but even more so.” (Gemma Galgani was

Passionist mystic nun who had died about twenty years before).

[106]

On July 20, 1920 prof. Giuseppe Bastianelli, the physician of pope Benedict XV

was sent personally by him to examine the wounds of Padre Pio. He visited with

Padre Pio on July 22 and examined the wounds. He gave a favorable report on the

supernaturalism of the case.[107]

[108]

In 1920, Mons. Alberto Valbonesi, titular bishop of Memphis, Egypt, a Vatican

employee, visited Padre Pio and was very favorably impressed. He said that the

interview with Padre Pio had ‘compensated me for years of pain.”[109]

On September 7, 1920, Padre Roberto Nove di Bassano wrote that he had been to

San Giovanni Rotondo with a skeptical and indifferent attitude, but after

visiting with Padre Pio and closely observing his daily routine he had been

conquered by his serenity and simplicity, and had dropped all his preventions

against him.[110]

By summer the scene was one of pandemonium. The little church was invaded by

peasants, artist, writers, politicians, lawyers, doctors, journalists, curious,

fanatics, thieves, pickpockets, sick wanted to be cured, possessed wanting to be

freed.[111]

The church was not spared. People cut pieces from cassocks, chasubles, albs, and

anything that presumably had been used by Padre Pio, such as straws from chairs

were he had been seated. Whenever Padre Pio appeared in public they cut pieces

of his clothing.[112]

In April 1919 Padre Pio complained to Padre Benedetto that his breviary had been

stolen.[113]

[114]

People stayed around the convent for days, and since there were no hotels or

private homes outside the town a mile away, they slept under the stars, ate what

they could, and drunk well water.[115]

There was no sanitation and many were sick.[116]

The Capuchin friars deplored what was happening, including the publicity by the

press, forbidden by Canon Law.[117]

In the town of San Giovanni Rotondo things had changed dramatically since the

news about Padre Pio spread. One of the changes was that many faithful started

deserting the local parish and went to the convent for religious services. This

emptied the church in town and made some of the local clergy resentful. Don

Giovanni Miscio, don Giuseppe Prencipe and don Domenico Palladino accused the

friars of “putting Padre Pio on

display for the purpose of making money”. The Bishop of Manfredonia, Mons.

Pasquale Gagliardi, with jurisdiction over San Giovanni Rotondo, got informed,

noticed, and joined the action against the convent. They “bombarded the Vatican

with complaints about Padre Pio.” Gagliardi went to the Vatican deploring Padre

Pio’s horrible manner of hearing confessions” leaving the souls “in a state of

agitation”. He insisted: “Padre Pio is demon-possessed and the friars of San

Giovanni Rotondo are a band of thieves.” He added: “With my own eye I saw Padre

Pio perfume himself and put makeup on his face! All this I swear on my pectoral

cross.” He also state that Padre Pio habitually slept

in the friary’s guest room attended by young girls with whom he took

liberties. Gagliardi also charged that the friars were living in “unspeakable

luxury, and were raking in huge sums of money.[118]

In September 1919 a rumor spread that Padre Pio was going to be transferred. The

citizen made massive public demonstrations and stayed around to guard the

monastery day and night.[119]

[120]

On October 14, 1920 in a clash between opposed political parties on the square

of city hall in San Giovanni Rotondo, there were fourteen dead and eighty

wounded. The town got national attention. Padre Pio tried to promote

pacification between the parties.[121]

[122]

On June 21, 1921 a visiting priest was suspected by the people as the one

assigned to prepare for the transfer of Padre Pio, and they stormed the

monastery.[123]

[124]

The

Napoli newspaper "Il Mattino" reporting about Padre Pio

The

Napoli newspaper "Il Mattino" reporting about Padre Pio

For several months the stigmatization of Padre Pio was known only to few people.

Than he news spread, and pilgrims and curious arrived at the convent, from

Southern Italy, then from the whole Italy and from abroad.

[125]

On May 9, 1919 the “Il Giornale d’Italia” was the first newspaper to report

about Padre Pio.

On June 1, 1919 “Il Tempo” run a title “Il miracolo di un Santo” describing he

instantaneous healing of a soldier by Padre Pio. The article had been written by

Adelchi Fabbrocini. On June 3, 1919 the same paper “Il Tempo” titles “I miracoli

di Padre Pio a San Giovanni Rotondo”, reports some prodigies attributed to the

friar. Also reports that “at times his body reaches temperatures of 50 C (F 122)

as it has been observed with bath thermometers).”[126]

On June 20 and 21, 1919, the journalist, Renato Trevisani, on the Napoli’s

newspaper “Il Mattino”, in full page describes that “Padre Pio, ‘The Saint’ of

San Giovanni Rotondo, makes a miracle on the person of the town’s chancellor.”[127]

[128]

[129]

On June 19, 1920 the “Daily Mail” reports “extraordinary events happening daily

in San Giovanni Rotondo”, and describes how the wounds had been investigated by

the doctors and prelates“. On October 27, 1923 the Belgian newspaper “Le Soir”

describes the wounds, the examinations, the prodigies and the “very high fevers

of 48-50C “(118-122 F).

The palace of the Holy Office in Vatican

The palace of the Holy Office in Vatican

Meanwhile the Vatican office of Inquisition, called at the time The Holy Office,

received contradictory information regarding what was going on in San Giovanni

Rotondo, about the nature of the wounds, the presumed holiness of the

stigmatized, and the behavior of the friars. The Holy Office was forced to take

a stand and initiated an exhaustive formal investigation.[130]

[131]

[132]

In 1920 the theologian Joseph Lemius of the Oblates or Mary Immaculate was

entrusted directly by the secretary of the Holy Office, Cardinal Rafael Merry

del Val.[133]

Lemius was asked a very precise question: “That measures, if any, should be

adopted by the Holy Office regarding Padre Pio da Pietrelcina.[134]

Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val, now Servant of God

Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val, now Servant of God

From the fall of 1920 to January 1921 he read the documentation available. In a

meeting at the Holy Office on January 21, 1921 he stated that without direct

examination on site nothing could be said for sure about the origin of the

stigmata.

Fr. Lemius suggested to send an Apostolic Visitor to be sent as a Qualificator,

to do a thorough investigation about Padre Pio’s moral, ascetic and mystical

character, focusing on humility and obedience, his way of dealing with women,

use of pharmaceutical products such as the carbolic acid he requested in

connection with the injections administered to the novices during the epidemic

of the Spanish fever.[135]

[136]

On April 26, 1921 the choice of the Holy Office fell on Msgr. Raffaello Carlo

Rossi, bishop of Volterra. He would have to answer the question on who really is

Padre Pio. He declined at first, than accepted the task. Mons. Rossi first went

to the Holy Office in Vatican were he examined Padre Pio’s file, full of praise

and criticism, then he went to San Giovanni Rotondo on June 14, 1921.[137]

Padre Raffaello Carlo Rossi

of the Order of the Discalced Carmelites

Padre Raffaello Carlo Rossi

of the Order of the Discalced Carmelites

In 1921, The Holy Office ordered the first Apostolic Visitation concerning Padre

Pio. The bishop of Volterra Raffaello Carlo Rossi, future cardinal, was sent to

San Giovanni Rotondo. He started on June 14, 1921, and left after eight days.

Padre Pio was 34 years old. Mons. Rossi had formal interviews with two priests

of the local parish: archpriest Canon Mons. Dr. Giuseppe Prencipe and bursar

canon Domenico Palladino. He also interviewed the friar padres Lorenzo, Luigi,

Romolo, Lodovico, Pietro, and Cherubino. Last, he had formal interview and

examination of the wounds of Padre Pio.[138]

From Mons. Rossi’s written report: “Padre

Pio is a good religious, exemplary, accomplished in the practice of the

virtues.”[139]

"In conversation, Padre Pio is very pleasant; with his brothers, he is serene,

jovial, and even humorous."[140]

"The religious Community in which Padre

Pio lives is a good Community and one that can be trusted."[141]

"The very intense and pleasant fragrance, similar to the scent of the violet, I

have smelled it."[142]

"I have examined the monk's cell and

could find nothing that would cause such a scent. There was only plain soap."[143]

“He has attested in a sworn statement to never using, and never having used,

perfumes.”[144]

Padre Pio told Mons. Rossi under oath: "On September 20, 1918 I saw the Lord in

the posture of being on a cross, lamenting the ingratitude of men, especially

those consecrated to him. He urged me to

partake of his sorrows, and to work for my brothers’ salvation. I asked him what

I could do. I heard this voice: 'I

unite you with my Passion.' Once the vision disappeared, I came to my

senses, and I saw these signs here, which were dripping blood. I didn't have

anything before."[145]

Mons Rossi: "The stigmata are there: We are before a real fact that it is

impossible to deny."[146]

"I am fully in favor of their authenticity, and, in fact, of their Divine

origin."

"The future will reveal what today cannot be read in the life of Padre Pio of

Pietrelcina." The report, called “Votum on Padre Pio da Pietrelcina” was

completed on October 4, 1921 and given to the Supreme Congregation of the Holy

Office.[147]

“On the wounds I used iodine every once in a while, but a doctor told me that it

could irritate them even more. They had me to use petrolatum jelly when the

wounds would lose their scabs. It may be over two years that I have used nothing

at all.”[148]

America

brother Bill Martin, later Father Joseph Pius

America

brother Bill Martin, later Father Joseph Pius

Padre Joseph Pius, Bill Martin before becoming a Capuchin friar, reported: “The

wounds were in the center of the palm, and the coagulated blood covered the

whole hand. The blood was always running out of the holes. It is true that if

you were very close and there was a light behind his hand you could see a light

shining through the holes. Mrs. Emilia Sanguinetti, said that when Padre Pio

celebrated Mass and held up his hands to bless people, she would see the light

through his hands. His feet were always very swollen. They were like melons

under his socks, one more swollen than the other. On the last day I did find

white crusts with a tone of pink, very pale pink, after last Mass on September

22. I took them away. When he died there were no scars.”[149]

Padre Pio to Mons. Rossi: “The wounds don’t always keep the same appearance. At

times they are more noticeable, at times less so. Sometimes they look like they

are about to disappear, but they didn’t, and then come back, flourishing again.”[150]

Mos. Rosi: “Do you swear on the Holy Gospel that you have not, directly or

indirectly, produced, nurtured, cultivated, preserved the signs?” Padre Pio: “I

swear! Quite the contrary! I would be very grateful if the Lord relieved me of

them!”

Sign on the house were Mos. Rossi was born in Pisa

Sign on the house were Mos. Rossi was born in Pisa

Mons. Raffaello Carlo Rossi, born in Pisa, Italy, was a religious of the Order

of the Discalced Carmelites. He served several Popes in many assignments in the

Roman Congregations, including the Holy Office. He was elected bishop of

Volterra and later Cardinal. Mons. Rossi saw Padre Pio’s holiness well before

many others who would follow him. He was the first to verify on behalf of the

Holy Office, the theological nature of the stigmata.[151]

He too, like Padre Pio, had an intense saintly life. Currently he is Servant of

God, and the process of sainthood is well under way.

Agostino, d. S. (2012). Diario. San

Giovanni Rotondo: Edizioni Padre Pio.

Ago12

Alessando, d. R. (Saint Pio of Pietrelcina.

Everybody's Cyrenean). 2010. San Giovanni Rotondo: Edizioni Padre Pio.

Ale10

Allegri, R. (1998). Padre Pio, un santo tra

noi. Milano: Edizioni Mondadori.

All98

Andrea, G. S. (2008). Padre Pio. L'ultimo

sospetto. Edizioni Piemme.

And98

Capuano, P. (2012). Con p. Pio: come in una

fiaba. Foggia: Grafiche Grilli.

Cap12

Casacalenda, P. P. (1978). Le mie memorie

intorno a Padre Pio. San Giovanni Rotondo: Edizioni Padre Pio.

Paol78

Castelli, F. (2011). Padre Pio under

investigation. The secret Vatican files. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

Cas12

Chiron, Y. (1999). Padre Pio. Una strada di

misericordia. Milano: Figlie di San Paolo.

Chi99

DeLiso, O. (1962). Padre Pio. New York:

All Saints Press.

DeL62

Duchess Suzanne, o. S. (1983). Magic of a

Mistic. Stories of Padre Pio. New York: Clarkson N. Potter.

Duc83

Flumeri, G. D. (1995). Le stigmate di Padre

Pio, Testimonianze e relazioni. Edizioni Padre Pio.

Flu95

Giannuzzo, E. (2012). San Pio da Pietrelcina.

Il travagliato persorso della sua vita terrena. Book sprint edizioni.

Gia12

Ingoldsby, M. (1978). Padre Pio. His Life and

Mission. Dublin: Veritas Publications.

Ing78

Malatesta, E. (1999). La vera storia di Padre

Pio. Casale Monferrato: PIEMME.

Mal99

Mortimer Carty, f. C. (1973). Padre Pio the

stigmatist. TAN Books.

Mor73

Napolitano, F. (1978). Padre Pio of

Pietrelcina. A brief biography. San Giovanni Rotondo: Edizioni Padre Pio.

Nap78

Peroni, L. (2002). Padre Pio da Pietrelcina.

Borla.

Per02

Pietrelcina, P. P. (2011). Epistolario I

Corrispondenza con i direttori spirituali (1910-1922). San Giovanni Rotondo:

Edizioni Padre Pio.

Epist. I

Pietrelcina, P. P. (2012). Epistolario IV,

corrispondenza con diverse categorie di persone. San Giovanni Rotondo:

Edizioni Padre Pio.

Epist IV

Preziuso, G. (2000). The life of Padre Pio

between the altar and the confessional. New York: Alba House.

Pre00

Pronzato, A. (1999). Padre Pio, mistero

doloroso. Editore Gribaudi.

Pro99

Riese, Fernando da (2010). Padre Pio da

Pietrelcina crocifisso senza croce. San Giovanni Roronto: Edizioni Padre

Pio.

Fer10

Ruffin, C. B. (1991). Padre Pio: the true

story. Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor, Inc.

Ruf91

Schug, J. O. (1987). A Padre Pio Profile.

Petersham, MA: St. Bedès Publications.

Sch87

Winowska, M. (1988). Il vero volto di Padre

Pio. Milano: Edizioni San Paolo.

Win88

[1] Gia12, 105

[2] Scg87, 112

[3] Gia12, 105

[4] Epist. I, 874

[5] Pre00, 87

[6] Sch87, 116-7

[7] Epist. I, 1054

[8] Gia12, 127

[9] Ruf91, 153

[10] Gia12, 203-4

[11] Cas11, 63

[12] Cas11, 223 and 204-5

[13] Cas11, 205

[14] Ruf91, 156

[15] Fer10, 133

[16] Gia12, 127

[17] Ale10, 84

[18] Epist. I, 1065

[19] Epist. I, 1068

[20] Epist. 1, 1068

[21] Duc83, 50

[22] Gia12, 128

[23] Per02, 248

[24] Ruf91, 155

[25] Per02, 248-252

[26] Ing78, 66

[27] Fer10, 134

[28] Fer10, 134

[29] Gia12, 127

[30] Per02, 252

[31] Pre00, 105

[32] Cas11, 154

[33] Ger95, 141-2

[34] Ger95, 143-4

[35] Pre00, 109-10

[36] Ger95, 143-4

[37] Ruf91, 163

[38] Ruf91, 154

[39] Pro99, 91-4

[40] Paol78, 70-75

[41] Cas11, 297

[42] Epist. I, 1090-1

[43] Epist I, 1091

[44] Epist. I, 1093

[45] Epist. I, 1106

[46] Gia12, 135-6

[47] Epist. I, 151

[48] Ago12, 58

[49] Ago12, 58

[50] Ago12, 341

[51] Gae08, 23-4

[52] Gia12, 140

[53] Paolino, 54-57

[54] Ger95, 147-151

[55] Ger95, 147-151

[56] Ger95, 147-151

[57] Ger95, 147-151

[58] Ger95, 147-151

[59] Fer10, 147-9

[60] Pre00, 112-4

[61] Pre00,124

[62] Fer10, 149-52

[63] Gia12, 145-9

[64] Ger95, 173-179

[65] Fer10, 153-4

[66] Pre00, 115-6

[67] Gia12, 150

[68] Mor73, 288-92

[69] Ger95, 179-273

[70] Mal99, 347-55

[71] Pre00, 117-8

[72] Fer10, 154-60, 170-1

[73] Fer10, 171

[74] Ger95, 173-179

[75] Win88, 71

[76] Ger95, 173-273

[77] Cap12, 393

[78] Del62, 79-80

[79] Win88, 71

[80] Ger95, tav, 17-20.

[81] Ger95, 10-22

[82] Cas11, 77

[83] Pre00, 123

[84] Mal99, 316

[85] Nap78,45-6

[86] Ruf91, 179-80

[87] Mal00, 317

[88] Pre00, 119

[89] Gia12, 175-6

[90] All98, 318

[91] Mal00, 319-20

[92] Pre00, 124

[93] Per02, 283

[94] Epist. IV,39 Note2.

[95] Ale99, 318

[96] Mal00, 318-9

[97] Epist IV, 40

[98] Cas11, 5

[99] Ruf91, 178

[100] Chi99, 152-3

[101] Pre00, 119-21

[102] Ruf91, 179

[103] Ruf91, 179

[104] Per01, 263-4

[105] Mal00, 319

[106] Pre00,

124

[107] Ruf91, 179

[108] Chi99, 153-4

[109] Ruf99, 179

[110] Chi99, 154

[111] Mal00, 326

[112] Gia12, 166

[113] Ruf91, 168

[115] Per03, 272

[116] Mal99, 263

[117] Pre00, 123

[118] Ruf91, 169, 183, 190

[119] Pre00, 123-4

[120] Per02, 282

[121] Chi99, 161-2

[122] Per02, 274

[123] Pre00, 124

[124] Per02, 282-3

[125] Fer10, 145-6

[126] Gia12, 143

[127] Cas11, 86

[128] Fer10, 146

[129] Mal99, 123

[130] Mal99, 134

[131] Gia12, 140

[132] Cas11, 5

[133] Cas11,64

[134] Cas11, 5

[135] Gia12, 204-5

[136] Cas11, 6

[137] Gia12, 206

[138] Cas11, 232

[139] Cas11, 27

[140] Cas11, 94

[141] Cas11, 132

[142] Cas11, 124

[143] Cas11, 125-6

[144] Cas11, 126

[145] Cas11, 202

[146] Cas11,107

[147] Cas11, 81-133

[148] Cas11, 201

[149] Sch87, 62-3

[150] Cas11, 231

[151] Cas11, 272